Using Mindfulness to Navigate “Self”

“I think, therefore I am,” doesn’t mean I am my thoughts, nor does it mean that you are yours. Even though Descartes believed, “If I am thinking then I must exist…” other philosophers later pointed out that the thoughts might be coming from somewhere else (although I’m not sure where that somewhere else is) so all we can really say is: “there are thoughts.” If you’re not your thoughts—a terrifying idea for some, a gift to others—what are you? We’ve been trying to answer the question of what it means to be human for centuries.

A couple of ways of thinking about what it is to be a sentient mammal in an increasingly secular world can be found within contemplative psychology or in Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT). The former describes us as a “heap” or aggregate of body (form), feeling (the tone of experience before thinking begins: pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral), as perception (naming or memory), as mental formations (thoughts, emotions) and consciousness (defined as contact with the senses and the objects of their awareness). CBT looks at us as a composition of thoughts, emotions, body, and behaviours. Thoughts, then, are simply one part of what it is to be us. In fact, the view of both models is that we are not fixed entities but dynamic processes that are always in flux.

Self: Fixed and in Flux

This idea if taken too far might lead us astray, untethered and disconnected from our day-to-day existence. If we didn’t have a fixed identity, then who makes dinner, drives the car, or colors his or her hair? Another way of navigating “self” is through the lens of neuroscience. At a recent mindfulness conference in Toronto, Norman Farb, a neuroscientist who studies human identity and emotion, and has a particular interest in mindfulness talked about the need for both a stable sense of self, assisted by the medial pre-frontal cortex and the ability to adapt and have awareness of changing momentary experience involving the insula. This makes sense, because too much self and we’re likely rigid. Too much change and we are chaotic. In order to function and adapt, we need both.

One of the reasons we suffer is because we hold tightly to a fixed view of self. We believe everything we think about others and ourselves. While this may have some socio-biological utility and may in fact be essential to navigating our internal and external world, it also often contributes to our misery. For example, holding tightly to a view of racial superiority may have helped us to protect our particular tribe when anyone not like self could have been a threat. However, as per recent events involving Black Lives Matter, recognition of our interdependence versus emphasizing difference and the mistreatment of those perceived as such could be the antidote to the effects of prejudice.

If we are depressed we think, “I am a depressive,” versus “depression sometimes gets a hold of me.” If we lose a loved one through a break up, we may think, “I’ll never love again,” versus “I’m grieving and this will pass.” If we are studying to become a physician, lawyer, or psychologist, we may be plagued by the thought, “I am incompetent,” rather than “I am learning and have no experience.” Our reactions to difficulty and our perspective narrow around our options about how we might respond more skillfully to life’s vicissitudes. And we all get our fair share of strife, some at the front end, some at the back end, and some in the middle. I forget who said this but it was obviously someone wise. Remembering this can help us not take pain and loss as an end point. That doesn’t mean we don’t feel pain but rather it doesn’t have to result in a deep hole from which we can’t climb out or have to define us.

How Mindfulness Helps You Navigate Difficulty

Mindfulness is a model of mind or if you prefer, of what it is to be human. We can think of mindfulness as a conceptual model, conveying the principles and functionality of what it is to be a person. As a model it helps us to understand elements of the human experience. Mindfulness is the map, not the territory. The territory is the experience itself. (I know this is heresy for those who think of it as truth). Shapiro S. et al, (2006) created a way of thinking about the potential mechanisms of mindfulness with respect to how it helps free us from adding to those inevitably painful times that befall us.

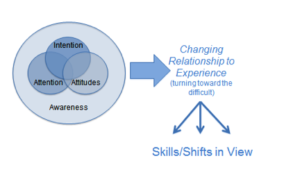

This model includes the marine life of intention, attention, and attitudes all floating in the sea of awareness that is us:

- Intention allows us to be deliberate about where we place our attention, thus creating choice in what we attend to, developing the ability to shift and hold it as needed. Mindfulness trains attention to be focused, open, and receptive.

- Focused attention allows us to disrupt negative, ruminative thinking such as, “I’m such a failure because someone criticized my work” by bringing attention to an object of awareness such as the sensations of breathing in the body or other body sensations. This is not suppression but rather redirection. Open and receptive monitoring of attention allows us to catch destructive thoughts and early changes in mood or increases in anxiety before they take hold, allowing us to take care of ourselves.

- Attitudes of curiosity and kindness enable us to turn toward difficulty and to get interested in what is happening, rather than attempting to avoid or push away what we don’t like.

Stephen Hayes, a psychologist well known for his work in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, discusses the power of avoidance in his bookGet Out of Your Mind and Into Your Life. Avoidance is powerful because it works so well in the short term. However, it has the added problem of perpetuating our problems and limiting our lives. For example, if you get invited to a party and you have social anxiety, you will likely choose not to go. What happens next? You may feel ashamed but the anxiety vanishes in a heartbeat. This is incredibly reinforcing. Willingness to have what we don’t want instead of defaulting to our habitual patterns of reactivity and avoidance is essential to opening to new possibilities and to learning that we can build tolerance and manage in those times when we would rather not. As below, turning toward the difficult (aka exposure) allows difficult emotions to surface and pass.

Mindfulness helps us learn to develop new skills and shift unhelpful views. We often come to reframe our perspective, to cognitively re-appraise that which at first may have been personalized (“It’s all about me”) as in the woman who gets distracted in her car and bumps the back of yours, giving you a whiplash. This happened to my husband recently and the woman, with a baby in the car, was distraught both about hitting him and because she felt she’d failed in her most important job of looking after her child. She couldn’t believe my husband wasn’t the least bit mad at her. He thought, “Come on really, I didn’t think she did it on purpose.” We learn to see that everything that happens in life is actually impersonal. This can be a difficult concept when events that transpire can feel so personal, such as the catastrophic illness, police brutality, or other violence. When we get struck by cancer, we sometimes say, “Why me?” The question perhaps to ask is, “why not me?” Cancer is a disease resulting from a number of variables; some mixture of genes, environment and perhaps psychology but it really has nothing to do with me as a person. Violence is equally the result of one person or many people’s biopsychosocial background, what might be happening on a given day, in a given moment. Thus the impersonal nature of experience can be the great leveller. It doesn’t mean that we don’t feel great pain or that terrible things don’t happen but reducing our personalization of everything that happens to us may help us begin to drop our prejudices toward others and ourselves and see how there is actually little separation between them and us. In fact, we’re all in the same boat, floating in that sea of awareness, from birth to death, making meaning, trying to survive, and not really taking in that nothing lasts. Mindfulness of body, thoughts, and emotions helps us to see that impermanence is our ally (until it isn’t). It takes the emotional charge out of situations that we may have previously thought would last forever (such as a depressed state, a bad relationship, a boring job). Sooner or later, everything ends. Again, our difficulty in internalizing this fact may speak to a survival advantage, from an evolutionary psychology point of view. Thinking things are permanent can be motivating. Responding mindfully means having the ability to move forward in any given situation uncontrolled by difficult emotions. In the words of mindfulness pioneer Jon Kabat-Zinn, “You can’t stop the waves but you can learn to surf.”

Mindfulness Practice: Noting Stressful Thoughts

Try this awareness practice taken from Cognitive Behaviour Therapy when stressful events threaten to overwhelm*:

- Identify the situation in one sentence. This helps stop you from getting lost in the story of how awful things are. Remember, just the facts, ma’am.

- Record the thoughts that are popping into your head unbidden, particularly the ones you wouldn’t want to tell an acquaintance. Thoughts usually appear in sentences or images.

- Label the emotions that you are experiencing. Emotions come in one word such as angry, sad, mad, happy, and scared, to name a few. Check for similarity with the thoughts you wrote down.

- Name the body sensations and check for parallels with the emotions you are feeling. For example, anxiety is often felt in the diaphragm or abdominal area.

- Write down any behaviours or impulses to act. For example, your partner tells you the relationship is over. This is the situation. The thoughts you have are, “I can’t believe this is happening. My life is over. I’ll always be alone.” The emotions are sad, angry, and scared. Your diaphragm feels knotted, teeth are clenched, and throat is tight. The behaviour is to turn on Netflix and make some popcorn so you don’t have to think about it.

- Look at what you have written.

- What do you notice and do you have any insights or reflections about what you wrote? As in the above example, you notice how you are catastrophizing, jumping into a future that has not arrived. You also realize that watching movies and eating popcorn are not a remedy for grief.

This exercise can help us to pause and parse tough experiences into manageable pieces. It increases our ability to see the interaction between the components of experience and can assist in allowing us to step back from our reactivity. We learn the language of our experience, developing the facility to articulate it more clearly. We can then decide whether we can let the situation go, let it be or address it, and if so, how?

* It’s worth doing many times. You may be surprised to see how often you react in a similar way, regardless of the difficulty you are facing.

– Patricia Rockman MD CCFP FCFP

This piece was originally published on Mindful.org as Using Mindfulness to Navigate Self

Patricia Rockman MD CCFP FCFP is an associate professor with the University of Toronto, department of family and community medicine; cross appointed to psychiatry. She is the past chair of the Ontario College of Family Physicians Collaborative Mental Health Network. She is a medical psychotherapist and leads leads MBCT groups. She has been educating healthcare providers in stress reduction, CBT and mindfulness-based practices for over 20 years. She is a founder and the Director of Education and Clinical Services at the Centre for Mindfulness Studies and the developer of the MBCT Core Facilitation Certificate Program.

The work of Shauna Shapiro is wonderful. But there is also a Buddhist view of the “mechanisms of mindfulness” that is also wonderful but very difficult to understand. I have practiced the traditional form of Buddhist mindfulness meditation for 50 years. (I am now 75 years old.) Advanced states of mindfulness meditation (developed from “the dhamma in the dhamma” in the Satipatthana Sutta) allow a person to view or consciously experience the unconscious mental processes (mechanisms of mindfulness, if you like) that cause the many benefits that years of mindfulness meditation produce. I will do my best to describe this kind of meditative insight.

First of all, I need to define the Buddhist concept of karma. In a Pali-English dictionary, you will find karma (kamma in Pali) is defined simply as “action.” The truth is that the Buddhist concept of action is very complex and refers primarily to mental actions. Starting with the concept of action developed by Alvin Goldman who viewed action (especially bodily action) as caused by an action plan consisting of a set of wishes and beliefs related to one another in a very specific and characteristic way, the Buddhist concept of the cause of action takes us back one more step to when we select the “best” action from a multitude of possible actions. In meditation, this is seen as a cluster of memories, beliefs, and desires or it can be seen as the product of a great deal of intelligence that can generate a collection of versions of a type of action in the twinkling of an eye. While many of the actions caused by this cluster are of no consequence (karmically neutral), the process of learning generally causes karma (decisions that define something in the world, something about ourselves, or something about another person) that has consequences (karma-vipaka) that are wholesome (kusala) or unwholesome (akusala).

Ordinarily, we learn very cautiously in order to avoid mistakes. The mind has various “safeguards” that avoid, detect, or correct errors in learning. And, as Elizabeth Spelke has discovered, we have a great deal of innate “core knowledge” that helps us avoid many errors. In Buddhist terminology, this innate safeguard is called the Bodhicitta, a very sophisticated intelligence that (1) guides the learning of the infant and child in matters of love and friendship in human relationships and human understanding, (2) unconsciously corrects mistaken attitudes that arise during mindfulness of breathing and is the cause of the kind of changes that occur during Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), (3) during more advanced states of mindfulness meditation, it generates “the body in the body” (called the “felt sense” by Eugene Gendlin) to guide the meditator to the historical origins of a complex karma formation (sankhara) and is there by the major cause of progress towards Enlightenment, and (4) becomes accessible to the conscious mind in important ways, providing extraordinary awareness, wisdom, and love and thereby one definition of Enlightenment.

We know that a dysfunctional or abusive family experience can profoundly distort mental function. Within the Buddhist understanding, this is understood to be caused by misrepresentations of reality and oneself by adapting intelligently to impossible family or other circumstances that may have occurred in a previous lifetime. The nature of this misrepresentation is unique to the individual. The development of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) is a very valuable development of mindfulness-based intervention (MBI).

A more fundamental form of MBI will flow from our knowledge of how to avoid the undermining of the intelligence of infants and children. The work of Maria Legerstee is especially relevant to this development.